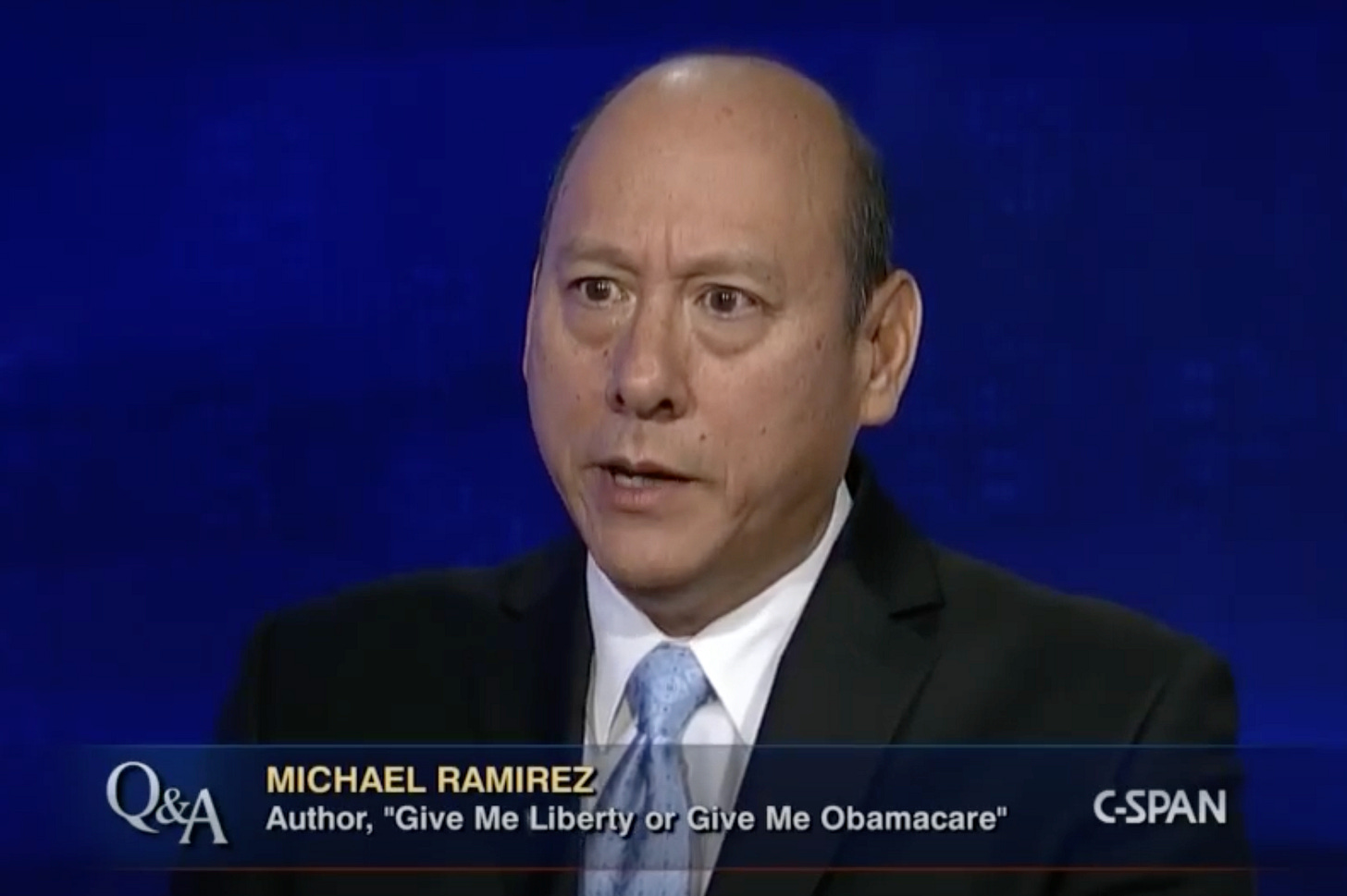

Michael Ramirez: CSPAN Interview

From America's Premier Editorial Cartoonist

Michael takes a break on Saturdays, so today, I’d like to share a wonderful CSPAN interview from 2015. You may click HERE to watch the hour-long video, and you can read the transcript below, or click HERE to read at CSPAN.

Make sure to subscribe and receive early delivery of Michael’s writing, exclusive peeks at his sketches, and subscriber-only perks like discounts on prints and t-shirts.

Click HERE to view video

Transcript:

BRIAN LAMB: Michael Ramirez, have you ever drawn a cartoon of Muhammad? And if you haven't, would you?

MICHAEL RAMIREZ: You know, I haven't. And I probably wouldn't, to be honest with you. You know, I don't do humorous cartoons for the sake of humor in the same way I don't do comic books with cartoons just for the sake of controversy.

The point of editorial cartooning is to try to reach a message to the audience that won't be overshadowed by the controversy surrounding it.

And I think where there might be an opportunity to use Muhammad, just the fact that having that in the cartoon would overshadow the point that I'm trying to make, will really take away from the effectiveness of the cartoon.

So, it's not that I'm opposed to using Muhammad, it's just that I'm more for assuring that the message that I'm trying to communicate gets to the audience.

LAMB: This is a personal question. And when I read this, that's the first thing I wanted to ask you about. We'll talk about your book of course. But are you really the brother to two sisters that are medical doctors and two brothers that are medical doctors?

RAMIREZ: I am. In fact, one of the other spouses being like nine people that are closely related that are all doctors. In fact, you know, Brian, the only way I can get the show up at family reunions is I say, well, you know, I deal with politicians and I deal with Congress. I'm sort of like a proctologist. And then they sort of let me into the family reunion.

LAMB: But go back to the -- two sisters and two brothers that are medical doctors and how many of their spouses?

RAMIREZ: Well, we got my older brother is a fertility specialist and his wife is not a doctor. She's the only one. All the other ones are doctors. And my grandmother and my grandfather were both in the medical profession. My grandfather was a physician in Japan. My grandmother was a pharmacist.

LAMB: Your mother and father?

RAMIREZ: Not. You know, in fact, I wanted to be, I wanted to be a doctor. I never wanted to be a political cartoonist. I wanted to be a cardiovascular surgeon. And I was saying this in a speech the other day.

You know, President Obama got a Noble Peace Prize for doing absolutely nothing. I should get one for all the lives I've saved by being a journalist instead.

LAMB: Go back to the beginning. You have a Japanese American mother and a Mexican American father.

RAMIREZ: Yes.

LAMB: How did that happen?

RAMIREZ: I'm half Japanese, one-quarter Spanish, one-quarter Mexican and completely confused. You know, my dad was in the military for 23 years. He was in army intelligence. And he met my mother in Japan. And so, she, she moved to the United States.

I was actually born in Japan, in Tokyo, Japan. Me and my older brother. The first language I spoke was Japanese.

And so, you know, it's been a long road. I've lived in all over the world. It's been good exposure because I've lived in Belgium for a year, Germany for two years, Paris for eight months and on and off between the United States and Japan.

LAMB: But the political cartoon came to you when?

RAMIREZ: You know, I never anticipated being a political cartoonist. It's the strangest part of this story is I really wanted to be a doctor. You know, I recall reading the newspaper every morning with my dad, we had two when I was living in California.

We took the Orange County Register and the L.A. Times. The L.A. Times had Paul Conrad and the Register had Jeff McNealy (ph). Jeff was working with I think the Richmond Times leader at the time.

But it -- they ran his cartoons. And that's a -- we had this morning ritual where we would have breakfast. He would the L.A. Times first. I would read the Orange County Register and half way through we would swap papers.

So I was aware of political cartoons and I loved political cartoons, especially -- and I loved Paul Conrad's dark images. They're just really moving and they had these deep messages.

And I think Paul took that a step further -- I mean, Jeff took that a step further with his wonderful sense of humor that I think extended the reach of the cartoon by reaching a much larger audience with the message. With the humor.

And so, like any other reader, I loved looking at the political cartoons, but I've never in my life envisioned me being a political cartoonist, I just stumbled into it by accident.

LAMB: We're going to show a whole bunch of cartoons from your new book.

RAMIREZ: That's great.

LAMB: But before I do that, this may have been -- this is your -- what, second book?

RAMIREZ: This is my second book.

LAMB: Second book. This cartoon may have been in your first book, but it's not in this one. And it was very controversial. You'll remember it, because the Secret Service came after you.

RAMIREZ: Right.

LAMB: But it's the cartoon -- you explain what it is.

RAMIREZ: Right. Well basically, I used an old photograph and very iconic photograph from the Vietnam war era, where the Saigon police chief had just caught this Vietnamese terrorist who had killed the Colonel and his family in Saigon and he basically executed them on the streets of Saigon.

I use that iconic image to portray George W. Bush being assassinated by politics during the advent of the, of the first Iraq -- well, the Iraq war I mean. And that image itself somehow got communicated to the Secret Service that I was advocating assassinating the president or something like that.

But honestly, I don't think I ever really was investigated initially. I think what happened was a drudge letter, a headline that said ,political cartoonist being investigated by Secret Service. And boy, when I got into the office at the L.A. Times, we were inundated with calls wanting to interview me on this conservative cartoon is being investigated by a conservative administration.

But I had really not been contacted by anybody in the Secret Service. In fact, at the L.A. Times, the general rule was all you have to do is call and start cussing and they would automatically forward you to my phone. And I am not really received any phone calls before this story broke.

And then, as it turned out, the L.A. branch of the Secret Service did end up contacting me, but it was only because we had this big publicity about me being contacted by the Secret Service and I think they felt left out.

And so, I got a call in the middle the day after numerous calls and this guy said, I'm with the Secret Service. I'd like to see you. And I said, well, you'll have to get in line. How do I know you're with the Secret Service?

Male: And he said, well, I've got dark sunglasses, a black suit and a black tie.

RAMIREZ: And I said, well, by all means, that proves it. Come on down. And I thought it was a crank call. And then 15 minutes later my secretary said, Mr. Ramirez, the Secret Service is here to see you.

And of course the -- I was willing to go down at SAMCA (ph). I couldn't remember any counterfeiting that I done, lately any ways. And the L.A. Times dispatched their lawyers, a team of lawyers down there and they promptly escorted him out of the building, because they -- we didn't want to set the precedent of having a journalist being interviewed by the Secret Service.

LAMB: With that, that particular scene -- there's eight -- we have 18 seconds of video. It was shot originally by Eddie Adams, an AP photographer and also somebody for NBC. Let's watch this 18 seconds to show how graphic this is.

RAMIREZ: Yes.

(Begin videoclip)

(End videoclip)

LAMB: How did you -- I mean you're not that old to know -- remember that, are you?

RAMIREZ: Right. One of the -- you know, I do. I do sort of remember it. I don't remember that entire clip of course, but back in television in those days, I don't think they showed the entire thing.

But I do remember the photograph as being an iconic image of the Vietnam War. And, you know, that's what political cartooning about. Using images that people are familiar with to relay a point of view.

LAMB: So, another controversy that you were involved in, was a...

RAMIREZ: I was involved in another controversy?

LAMB: Hate cartoons.

RAMIREZ: Yes.

LAMB: And that was -- and you were accused of showing the Western Wall, the Wailing Wall over in Jerusalem. And here it is on the screen.

RAMIREZ: Right.

LAMB: What was that cartoon?

RAMIREZ: It was kind of worshipping their God. And what I did was I took the, sort of the stones that looked, you know, sort of like the western, the Wailing Wall and I produced the letters H-A-T-E.

And it was at the time of the first intifada (ph) where I have this figure this kind of a conglomeration of extremist Israeli settlers and of people that were opposed to the establishment of a Palestinian state. The people who are kind of creating all the violent upheaval there.

In addition to that having, a, Palestinian figure, who have, if you, if you noticed, he's on a prayer rug but he has his shoes on. So both, these figures are sort of utilizing a false religion for a political purpose.

Instead of really pursuing a religious advocacy, I thought they were just worshiping hatred. And so this cartoon, when it appeared, I actually got numerous complaints from both sides. Both the Jewish groups were upset that I'd use the Wailing Wall figure and the Palestinian groups were mad at me because I was accusing them of hatred.

So, it just proves that once again I am an equal opportunity offender.

LAMB: When was the first time an editor -- and you were syndicated, so how many different papers at the -- are you syndicated now?

RAMIREZ: About 540 papers around the world so I get paid now in all languages right now.

LAMB: When was the first time an editor said, I'm not going to run that?

RAMIREZ: You know, I've only had one incident in my entire career. It was with my editor, Angus McCarron. Lionel Wender was the editor of the Memphis Commercial Appeal and he's the one who brought me over to Memphis where I won my first Pulitzer there.

LAMB: And you were there seven years?

RAMIREZ: I was there seven years and Lionel was killed an awful accident on New Year's Eve day and Angus McCarron took over from him. Angus was the editor of the Pittsburgh Paper. And the, the rumor was thick that, you know, Angus was very liberal and Lionel was very conservative.

But I was going to be one of the first people to go.

LAMB: Because you're conservative.

RAMIREZ: Because I'm I'm very conservative. In fact, we had, we had civic leaders lining up in his office for three days straight, telling Angus to fire me. And so we had, we had a pretty terrible beginning. In fact, he kicked me out of one of the editorial meetings.

Cause I like engaging in the editorial meetings and on the third day that he was there, on a, on Wednesday, the topic was on welfare reform and you know, they're trying to advocate working in order to get welfare.

So I did this cartoon where I had this Uncle Sam figure, lying in an alley, holding a cardboard sign that said, will work for food. And he's looking at the headline on workfare and he is turning to the bum next to him and he's saying, you mean they actually want me to work? Which was a totally legitimate cartoon.

Well, Angus canned it. And so, I went up to Angus and I, and I said, you know, this is a legitimate cartoon, I think it oughta run. And he said, well, it's not going to run in this paper. And I said, well, I mean, I'll send it to my syndicate and it's going to run in all my other papers.

And he said, fine, but it's not going to run in this paper. He used more explicit language than that. And so, I, I called up my accountant. I said, you know, we better get everything together. I think I'm probably leaving.

And a demand at a meeting was saying this on that Friday. And I went into his office and I said, look, you've got five illustrators in this newspaper that are better artists than I am. If you want them to draw what you want in the newspaper, then I think you'd oughta hire them and let them do your political cartoons. I'm an editorial cartoonist; my job is to think of these profound images, break them down into something that is very easy to present to an audience and understand, and give my point of view, and it has my name on it.

If you want to put your name on the cartoon, by all means, do. But I'm an editorial cartoonist, and I'm not going to draw your cartoons, I'm going to draw the best cartoons that I can.

You give me the freedom to do what I do best, I'll research these cartoons, I will substantiate them, I will do great editorial cartoons -- I'll win you a Pulitzer Prize, but I'm not going to draw your cartoons.

And if you're going to fire me, I want you to fire me right now. And (Angus) laughed at me, and he said, "Nah, nah. You can just do whatever you want."

And from that moment on, we got along great, and he gave me the complete freedom to do whatever I want. But that was the only incident where I had a cartoon killed.

LAMB: How long were you in the L.A. Times?

RAMIREZ: I was at the L.A. Times for about seven and half years.

LAMB: And what happened there?

RAMIREZ: You know, I think there was just a mutual parting of ways. They're looking for ways to cut costs. Philosophically, you know, it was never a very good fit, I don't think. We had talked about (Paul Conrad), my predecessor.

And (Paul) and I are as diametrically opposed philosophically as two people can be.

But -- and you know what, Brian? They actually wanted to limited the number of cartoons that I did every week. In fact, I had to negotiate upwards to try to do more cartoons.

And so, you know, there was a huge transition between publishers, and I worked for the publisher. And as the publishers came and went, I made the familiarity between me and the publishers left, as well. And there just came a point where they were looking to cost cuts, they wanted to change. I'm not sure they ever embraced my philosophy.

Probably the only job I had, outside of military service, where I had to put on Kevlar and a helmet to walk through the (news right).

LAMB: We'll talk about your new job at Investors Business Daily -- not new, new, but where you are now.

RAMIREZ: Yeah.

LAMB: But let's look at some of your cartoons from this book. This book is called, "Give Me Liberty or Give Me Obamacare." Why the title?

RAMIREZ: Well, you know, because they wouldn't let me put An Illustrated Guide to Impeachment.

But I think, when I look at this Obama administration and the things they have done, this massive expansion of government -- you know, we have $128 trillion in unfunded liabilities when it comes to entitlements, and 15 million more Americans that are on government aid.

I think, more than anything, that sort of gives the onus of what this administration represents -- to me, as a political cartoonist. A big government progressive regime, unlawful regime.

And what I'm proud about in this book is it really makes the case on all of the things that they have done wrong. And history -- past history is a good way to provide for the future. You know, we're getting into another presidential election cycle.

I'm hoping that, you know, this will spark the initiative for people who want real change to get back to our constitutional foundation government, to enact them, to them involved in the process -- because that is what political cartoons are, we're a catalyst for thought.

And to educate progressives who haven't seen clearly what the consequences of these disastrous policies have been.

LAMB: By the way, for folks that have -- don't know you're politics, one of the introductions in your book is from Dick Cheney, and the afterword is from Rush Limbaugh.

RAMIREZ: Yeah.

LAMB: So, there is no question where you are.

RAMIREZ: Right.

LAMB: But I want to show a cartoon.

RAMIREZ: Sure.

LAMB: This one is from 2008, and it's headlined there, "The 47 Million Uninsured."

RAMIREZ: Right.

LAMB: And for those that can't see it, the first figure says, "I can afford it, but I don't want it." And then there are 18 million underneath that person. "I'm 18 to 25 years old, and I'm indestructible." There are 8.4 million at the time. "I'm illegal and I'm not here," 12.6 million.

"I'm in between jobs and only temporary insured," 9.4 million. "I'm covered, but my parents have not signed me up yet," 8 million, and "I'm eligible for government health programs, but have not signed up," 3.5 million. And then you have little asterix, as up to more, because some categories overlap.

RAMIREZ: Right. You know, and this is the sad consequence of what I think the media is not doing its job. It's sad when a political cartoonist has to point out the factual basis of a relevant debate. You know, this 47 million figure has never been really proved -- proven by -- in fact, I think a week after the administration rolled out the 47 million who were uninsured, that they bought that number down to 37 million, because they really pulled it out of midair.

I think from what I've read -- and the -- it's sort of -- you know, the investigations that were done at the time, I think we were talking 4% people that were uninsured at the time.

LAMB: Here is another one from 2008, and you'll see it with a -- there's a woman standing there amateur overhead, and she says "I love Cornhuskers", and then you had two senators, women senators walking by. What's that?

RAMIREZ: Well, they're -- no, not two women senators. They prostitutes, that's right.

LAMB: No, I know, that's right, yes.

RAMIREZ: And Ben Elson saying, "Amateurs," and the prostitutes are saying, "Senators." And this is really on Obamacare the kind of gift-making and trading that was done to convince these senators to go along with this with -- this program. You know, they basically had to bribe and use chicanery in the process, change the rules to enact Obamacare, and so that cartoon really points that out.

LAMB: Here's one from 2010, "Tell us about the Mad Hatter."

RAMIREZ: Well, the Mad Hatter is a Nancy Pelosi and she's saying it -- you have to pass this bill so that you can find out what's in it and this is the most ethical Congress ever. And once again, it was on -- based on this Obamacare scheme that this administration was going to push through, utilizing whatever methodology they could.

And this complicated, complicated bill that nobody had ever read was going be passed and thrown onto the American public without really knowing what was in it, or what the consequences of what was in it was happened the population.

LAMB: The cut line on this is, please remove these items from your person, and it is from 2010.

RAMIREZ: Right. And this is on the debate that's going on today, which is on the Fourth Amendment how far do we go to protect our general public, and what constitutional rights do we have to exchange for safety? Which is, you know, there is a real question as to the extent of that.

Now, the thing that defines America is our Constitution and the liberties that we have and freedoms that we have. And hopefully the fear of this danger from these terrorist groups will not overcome our common sense to redefine what America is.

LAMB: Up there in the corner on that badge it says, "TSA" and then inside it says, "U.S. Department of Groping."

RAMIREZ: Yes, and that was when you had a number of stories where TSA guys were getting a little bit touchy-feely, but I heard a bunch of them got a bunch of phone numbers, too, so that was a good thing for them.

LAMB: Here's 2014 "The Police Keeping us Down," explain this and what your -- the art of this and what you're trying to do for the person that picks this up in the newspaper.

RAMIREZ: Well, you know, the juxtaposition of the reality of what's going on in the black community, which is the vast majority of homicides and killings were done by black-on-black crime, and yet there are some of their civic leaders that are blaming it on the police.

And as we've seen, you know, just recently in the cases with the San Bernardino and the policeman who led these people that could have been hostages, saying, I'd be willing to take a bullet for you first, the police really have a terrible, terrible job keeping us secure it. And it's just made harder by this movement that is blaming them for the irresponsible behavior of other people.

Now in certain circumstances, obviously, the police ought to be condemned for their overzealous zealousness, or the horrendous things that have happened. But in the vast majority of circumstances, they are there to keep us safe. People should be reminded of that.

LAMB: Here's 2012, and it says the cut line Is A Darkness Rising. And explain this one?

RAMIREZ: Yes. Now, this one was on -- this is really directed toward a new generation of folks that are being brought up in a different way than perhaps, you know, and I were, where we had a family unit, there was a cohesion. There's kind of a person-on-person relationship; where the new millennials have a lot of violent video games, they communicate in ways where they -- they don't really see people anymore.

And I think when we have this incident, which was -- this cartoon was about the shooting in Colorado -- the question -- and the Batman movies -- the question was what -- what changed this person into this monster. The lack of communication, the lack of human contact, playing these violent video games.

These are all questions for generation Y.

LAMB: This next on is complicated, you know, if you're sitting at home watching at, it would be hard to see it, but it's from 2012, and the headline on it is A Weapon Guide for the Uninformed, and average homicides or deaths per year, per category, and off on the left there, you have what looks like an AR-15 semi-automatic.

This rifle is the same as -- and then below, it says military-style assault rifles, mass shootings 18. Now, is that 18 people at that time?

RAMIREZ: Yes. At the time when I did this cartoon, I wanted to compare the homicide rates, and what -- what type of instruments of murder are used and what the damages.

And you know, the problem with the -- with some of the progressive media, I think is, they exaggerate things to sort of fulfill their political agenda, like this idea that these weapons that look like assault rifles, are in fact assault rifles. And there's a big difference between, you know, an automatic weapons, where you squeeze the trigger and it fires off many rounds, and these long rifles which are the same as any kind of hunting rifle that you, when you squeeze the trigger, it just shoots one bullet.

So, I wanted to compare and contrast how many murders are done with other instruments, and in this cartoon, you can see that you know, blunt objects -- handguns, which nobody's talking about banning, drunk driving, people using their hands and feet in violent acts, auto accident, constitute far more deaths than these mass shootings.

LAMB: For those hearing and not watching, auto accidents 32,000, rifles 453 were killed, 6,009 people killed by handguns, 674 by blunt objects, and you have a hammer there, 1,817 by knives, drunk driving 10,839 and hands feet and fist, 869. That is in one year, I assume.

RAMIREZ: That's in one year and I think the statistics came from the FBI statistics. But you know what, if we're going to have a debate about these issues, you have to know the facts, they have to be grounded in fact. And let's put everything on the table, figure it all out, then figure out exactly what we're talking about.

LAMB: Cartoon here from 2009, and again the figures are kind of small. Explain what you see in this?

RAMIREZ: Well, you two Indians, and they are looking at the new invaders of the New World. And one Indians is saying the other, "Running Bear," not another word about immigration reform. Now, be polite to our visitors.

And of course, the motivation behind this is on immigration, and how the Indians probably didn't worry about immigration back then, and therefore now you see who is dominating the new world. It's kind of a tongue-in-cheek play on what's going in immigration. I think, you know, for some of us, there's a delineation between immigration and illegal immigration, just like there's a delineation between Islam and radical Islam.

Leaders that cannot figure out the difference between the two probably shouldn't be guiding our government.

LAMB: Got some liberal cartoonist -- and by the way, if you're stacked them all up, how many are going to be conservative in this country, and how many of them are going to be liberal?

RAMIREZ: Yeah, we're outnumbered probably -- probably nine-to-one, I would imagine. If there is one percent of the conservative cartoons out -- or 10% of the conservative cartoons out there, I'd be very surprise.

LAMB: Who are some of the other leading conservative cartoons?

RAMIREZ: Boy, there just aren't that many, to be honest with you, that I...

LAMB: Steve Benson?

RAMIREZ: No, Steve actually went the other way. He started out being very conservative, down in the Arizona republic, but then the debate that he had within his church -- which was a Mormon church, and he left the Mormon church. He's now very, very liberal. So, he's become very progressive.

You know, we're outnumbered. I mean, I could name you half a dozen progressive cartoonists that I love, liberal cartoonists.

But when it comes to conservative cartoons, there is only a handful. I mean, Gary Varvel in Indiana, Scott Stantis, in Chicago -- which is probably more center right than far right.

There's a tone that have been retired or left their paper. But -- the McCoy brothers, Gary and Glen McCoy.

I think Nate Beeler, is probably center right. There just aren't that many.

LAMB: One of the most celebrated political cartoonists in at least my lifetime is a man named (Herb Lock), and they did a documentary of him at HBO.

Here is him -- (Herb Lock), he appeared on Book Notes in 1993. He is deceased, and when died he gave $15 million he turned at the Washington Post to the foundation. So here's a (Herb lock).

(Begin Video Clip)

Here's a cartoon from the year 1950, the headlight on it is, You Mean I'm Supposed To Stand On That, and right up here is the word "McCarthyism."

HERB LOCKE (PH): HERB LOCKE (PH): Yeah, apparently so, that's the first use made of that word that I know of, and I remember how it originated, because they wanted to put something on that (inaudible), and you couldn't call it McCarthy himself. And you wouldn't say McCarthy techniques or so, and I thought, well, maybe use one word, McCarthyism, and you know, it caught on.

(End Video Clip)

LAMB: So, how often has a cartoonist from your experience developed something like McCarthyism or some other term?

RAMIREZ: Yeah, it happens very rarely, I'd imagine. And be honest with you, I don't really look at other political cartoons at all.

LAMB: Never?

RAMIREZ: Well, you know, I do on a occasion when my cartoons are on a round up or something, and somebody says, hey, here's your cartoon, and there are other cartoons there.

But you know, we all deal with the same issues, especially with a 24 hour news cycle, with cable. I just don't want to see what my competition is doing, I -- you know, I'm -- I want to deliver a message to my readers, that's the most important thing in my mind, and I really don't want to see what anybody -- what anybody else is doing, because I think we're going to talk about the same subject matter.

And I don't want to subconsciously adopt their ideas or anything like that.

LAMB: How often do you find people that don't focus on what the politics are or cartoonists?

RAMIREZ: Well, you know...

LAMB: Or on the opposite, how often do you find people that really completely understand what you're trying to do?

RAMIREZ: Well, you know, I think -- you know, because you and I are into politics, we think in that way.

But I don't think the vast majority of Americans actually think in that light. In fact, I'm really surprised, as I give speeches around the country, and I give speeches all of the time, how closely unified the American people are on the majority of the issues.

And you know, they're divided on a lot of substantial issues, but for the vast majority of the things, Americans are very much closer together than people would think.

You know, I think there's people in political organizations, they have an agenda, they want to draw these people apart, because it helps them. But there are more things that unify us than divide us, I think.

LAMB: A cartoonist that has appeared here many times over the years, he's now 80 years old, still alive, Pat Oliphant.

Here is -- this was back in 2014, David McCullough is on the stage with him, but I want you to see what he does when he's drawing Richard Nixon, and right next to Richard Nixon is Lyndon Johnson.

RAMIREZ: Okay, great.

(Begin Video Clip)

David McCullough: Patrick, I get the feeling you have a good time doing that face.

Pat Oliphant: It comes back about once a year. It's a strange afterlife he has.

(Laughter)

David McCullough: I didn't know he was left-handed.

(End Video Clip)

LAMB: So, when you were growing up, what cartoonists -- besides Paul Conrad at the L.A. Times and others as you mentioned did you pay any attention to?

And what about the drawing part of this? You have -- I'm going to show one in a minute where you have a certain why that you draw. How would you explain the differences?

RAMIREZ: You know, my influences were whatever was running in the newspaper and the people that I liked the best.

Pat Oliphant was one of them. I think Pat is just a phenomenal political cartoonist.

And you know what? I can appreciate the art form itself, and what it's meant to be, which is a mechanism to influence people, regardless of what political party you're affiliated with or broad philosophy that you're affiliated with.

And Pat does it better than most anyone I know. I think Jeff was in the category, I think Paul -- yeah, Jeff MacNelly, was definitely in that category. Jeff is a good friend and sort of a mentor.

I loved Jeff's work. He added an element of humor, that I think was a great tool in expanding the audience of a political cartoon -- which is something that I try to utilize in my cartoons itself.

And Paul Conrad of course, because just the dark, you know, foreboding images that he had, but they would reach you and touch you. I think that's what good, effective political cartooning is all about.

You know, I -- I kind of view political cartooning almost like advertising on television, you know, you've got about five seconds to capture the viewer's attention, you've got another five seconds to deliver the point or to sell the product.

The only difference is with television, you're selling a product; with political cartoons, you're selling an idea.

And believe me, I believe that I'm trying to reach people; I believe that I'm trying to change people's minds, reinforce the ideas that they have for a purpose, which is my view of what the United States ought to be, what this self-governing Democratic Republic is all about.

The power of America lies in its people. And you know, less government, more people. The people should have the power, they should wield this power, because the kind of political celebrities that we have today, people forget, it's the politicians that work for the people, not the other way around.

LAMB: Back to some cartoons from your book, this is 2014, a familiar face will appear on the screen.

And how have you drawn her?

RAMIREZ: Yeah, Hillary has been great. In fact, I have to say the Clintons are probably my favorite political family.

You know, I won my first Pulitzer in '94 on the back of that administration. This cartoon where Hillary is saying, I Was Dead Broke, That Will Be $200,000, Please.

LAMB: She's at a podium.

RAMIREZ: Right, exactly. It's when she was professing, of course, not to have any money, and yet she was making $200,000 a speech.

The -- you know, the relationship that Bill has with his interns is probably the same relationship that Hillary has with the lack of being able to tell the truth. I think she makes for great political cartoons.

LAMB: But how -- you know, how -- did you draw her on purpose the way, you know, she has little tiny months and teeth.

RAMIREZ: Yeah, you know, when you take the -- a caricature of somebody in political cartooning, you're changing the dynamics of their features not only to make them into a cartoon, but to show sort of the dynamics of their personality as well.

If you notice in my President Obama cartoons, the more he is caught not telling -- you know, in prevarication, the larger his ears get.

So, it's reflected, and you can see that, in you know, Pat Oliphant's caricatures of Richard Nixon.

You know, as he got more immersed into Watergate, the shadows on his face got darker, and his eyes got darker. And pretty soon, they were barely eyes, they were just little black holes in his head.

LAMB: I remember asking Pat Oliphant years ago, he was not particularly friendly to the Jimmy Carter administration, and I asked him, how has Jimmy Carter changed in your cartoons over the years?

And he had a very simple answer, he said, he's gotten smaller.

RAMIREZ: Right.

LAMB: And at the end of that administration, he was tiny and in the corner.

RAMIREZ: Right, and that -- you know, that's a perfect device. You know, the one thing that we have over our journalist colleagues is we have exaggeration.

We get to create our own world, and the dynamic of that world reflects on what we're trying to say with the personalities.

LAMB: When did you go color?

RAMIREZ: I went color when I first started at IBD, when I left the L.A. Times.

LAMB: And it -- Investors Business Daily?

RAMIREZ: Yeah, Investors Business Daily, which, because I'm a capitalist prick, I have to say it's the best editorial page in the country, and...

LAMB: You write some.

RAMIREZ: Well, I do write some. You know, I get to co-manage the editorial page there. It has been an expansion of my duties, and frankly, we just -- we have great writers there.

The one thing I love about our editorial pages, we're not afraid to tell the truth. You know, people are giving praise to Donald Trump for his bluntness, but I've been doing that my entire career as a political cartoonist.

And we do that on the pages of Investors Business Daily, because we want people to have the facts out there, and then decide for themselves how they feel about things.

LAMB: And you're located where?

RAMIREZ: We're located in Los Angeles, but you know, we have offices all over the -- in New York and D.C., and I think our new printing plant is going to be in Texas, actually.

LAMB: I've seen -- last one I saw, about 156,000 daily circulation. Are -- is that hard, that hard copy?

RAMIREZ: Yeah, that's strictly print.

LAMB: Yeah. How much do you go digitally?

Michael Lamb: We used to -- well, you know, I don't know what the numbers are to be honest with you. But we've rapidly expanded digitally. But that's sort of the emphasis of our, our newspaper now. Because we're reaching so many more people that way.

LAMB: Here's a cartoon and it looks like you're cutting both sides.

RAMIREZ: Mm-hmm.

LAMB: I mean, there's a Erskine Bowles is in on the left and Alan Simpson, the senator, in the middle. The bowl Simpson, Simpson-Bowles commission and then you have a little kit over at the right with a -- his formulary...

RAMIREZ: Right.

LAMB: ... milk bottle, saying cut spending.

RAMIREZ: Remember, to convene this debt commission and to the -- I don't know how many millions of dollars they spent in putting this debt commission.

To figure out the solution to this now $18 trillion national debt that we have and Bolskin (ph) saying it's very difficult, Alan saying it's very complicated and a little baby saying just cut spending.

You know, it's amazing when you look back at our budgets, the last time that the George W. Bush was president, we had a Democratic majority in the House and the Congress. And he was roundly criticized for overspending which was right.

I mean, I did cartoons against that as well. But I was looking back at that, that number in the last year when, when you have that configuration. And the deficit was $160 billion with a B. Seven years later at the apex of the Obama administration, when they had a Democratic majority in the House and Senate that that deficit rose to $1.3 trillion.

That's not even to mention the growth in those seven years of how much federal spending increased during that period of time. I mean, I think at the time, it was like $2.4 trillion was the federal outlay and then it was almost 3 trillion, if not, over $3 trillion within seven years.

Population growth was like 4%. How big does this government have to be really? And when you when you read these endless stories about the duplication of services and Obamacare has basically become an expansion of Medicaid and is costing taxpayers a huge fortune.

And yet, they're not receiving better services. Now, with me, it's about having a smaller, more efficient government. And the realization that we have a finite amount of capital out there, you can divide it a couple ways. You can either give it to the people that innovate and create jobs and they use a dynamic economy to grow.

Or you can give it to bureaucrats that do nothing but shuffle paper and are inefficient at what they do.

LAMB: A cartoonists is deceased. We did an interview with him in 2008 who was probably as far left as you are right. I wanted to just -- I want to know what you think of this. He's talking about a cart -- he was not the same kind of a -- you saw him mostly in magazines like the New Yorker.

And I think he also drew for the New York review books. But anyways, David Lavine (ph), (audiogap).

RAMIREZ: Drew drawings of Henry Kissinger. I understand one of them was rejected by a publication? No, by all other than one publication, that is The Nation. In fact, The Nation was known among cartoonists that, you know, if you really had to try something or you wanted something that would be loaded political terms, this was the place to go.

And sure enough they printed Kissinger having sex with the globe being the head of a woman and it was to suggest sexually, this guy was screwing the world.

What do you think? Would you do something like that?

No, you know, IBD is a family news paper, so I think there's limitations to what we do and I want to reach as large of an audience as possible. But -- and I haven't seen a whole lot of what David has done and mostly he does characters.

LAMB: Yeah.

RAMIREZ: But their really beautifully rendered, you know, I really love them. You know, I, I, I am a, you know, hard right winger I guess you could say, very conservative.

But I'm looking at these, these issues on their merits and I -- it's not about personalities. I, I mean I'm an equal opportunity offender. But it's about when you make these drawings, how will it translate out to the audience and how many people can I reach?

And I think if you do something too crass. It's going to be limited. Now, of course you could get controversy about it, but the controversy itself isn't always good. Sometimes it overshadows the point you're trying to make.

And sometimes the hardest decision for an editorial cartoonist is really, not running a cartoon. For instance, there, there was a period when Johnny Cochran died, I thought of this great cartoon. The first image I thought of was Johnny Cochran in heaven.

And of course Johnny had gotten O.J. Simpson off on a murder charge. And so he's at gates of heaven and St. Peter's saying, I'm sorry Johnny if the halo don't fit, we don't admit. It was a natural idea, but you know, upon investigating who Johnny Cochran was, seeing all the things that he done.

He was a very generous person involved in various charitable activities, I couldn't define the man by one single action. So with political cartoons, it's almost just as important to decide what not to draw as it is what to draw.

LAMB: Here from 2012, the cutline is, and there's plenty more where that came from, we'll see it in a second. What's this?

RAMIREZ: Right. This is a, this is on turning corn into ethanol. You know, one of the byproducts of that -- and we can go into the details of the inefficiency of using corn -- basically corn-based fuel, because it takes so much farmland to, to create it.

What they didn't realize was in doing this, you also limited the supply of food out there for Third World (ph) countries and that they were caught making the cost of corn actually rise because they're using -- utilizing corn for ethanol. And so, I decided to juxtaposed that to the conditions that are going on in third world (ph), where corn is a very, very important element for them to survive.

And yet we're doing it because we want to push this movement toward fuel -- toward alternative fuels, even when it's inefficient in its creation. So I was just showing you the side effect of that.

LAMB: I read an account in your University of California Irvine alma mater publication that you used to have Bill Clinton -- an imitation of Bill Clinton on your telephone answering service.

RAMIREZ: Yeah. You know, one, one of my, one of my dearest friends is Paul Shanklin who does the voice impersonations on the Rush Limbaugh show. In fact, I discovered Paul of all places in Memphis, Tennessee.

And I was invited to play golf and I have to tell you, you know, I, I surf, cause I'm from California the surfing in Memphis stinks so I had to find an alternative...

LAMB: On the Mississippi River?

RAMIREZ: Right. And so a friend of mine invited me to go play golf with a couple's friends and it was the first time I'd ever -- I never played golf. And fortunately, there was one person who is more physically inept with a golf club then I was.

And so I was leaning down to putt, and all the sudden I heard Ronald Reagan coaching me on this putt and it was Paul. And boy, he is just an amazing impersonator. And, and, so I, I I, hooked him up with the Rush Limbaugh show and so now he's doing the Rush Limbaugh show.

But Paul, every once a while, I would get him to record my answering machine and do different voices for my answering machine. Now I made a mistake once of giving him my code for the answering machine and the -- and I actually had to get rid of that answering machine.

Because you would - he would, in the middle of the night change my messages and that created all kinds of problems. In fact, on Sundays when I was doing USA Today for Monday's Paul and I would get together and we would talk about parodies and skits for songs, and song parodies.

And then when I'm starting to draw my cartoon, you know, I become focused and I just ignore everything. And unbeknownst to me, Paul would answer my telephone as me and later on in the day, I would have friends calling me back saying what kind of medications are you on because you were just speaking gibberish.

And I would say, well, I haven't spoken to you today at all. And it was Paul answering my phone as me so if you want an obnoxious friends, there's one for you right there.

LAMB: A couple of years ago, former Vice President Al Gore sold his television network, Current TV to Al Jazeera for reportedly $500 million. And you have a cartoon back in 2013, explain this one.

RAMIREZ: Right, where Al is saying, so...

LAMB: I can read it. I can -- so I sold my station to anti-American network, funded by an oil-rich Arab state. I always said I was for a green economy.

RAMIREZ: Right. I mean, it was kind of I, I ironic that Al Gore who was supposedly for the green movement turned out to be more of a capitalist than an environmentalist in this circumstance in fact. You know, I almost openly wept when Al Gore didn't win the presidency because I think that would've been a fine thing for editorial cartooning.

LAMB: The next cartoon is from 2014 and it's very complicated. It says on there -- starts out with global cooling with a line through it. It's on a blackboard. Global warming, a line through it. Climate change, a line through it and then climate disruption underlying.

Well, explain this one.

RAMIREZ: Well this is the, this is the, you know, the rename, the rebranding of the global, or I should say, the, the climate movement. You know first they were called global cooling back in the '70's. Now they're called global warming. But then, the earth hasn't warmed for the last 15 or 20 years, so now they have to change it to climate change.

And now that -- even that wasn't getting up because people were making fun of that so they wanted to change it to climate disruption. And then the little kid is writing on the bottom corner of the chalkboard, it's called weather.

And other side of it, you write -- you have to see this up close, so then you have to buy your book.

Yes, exactly.

LAMB: It says the climate is warmer and that's crossed out and below it, it says cooler for now.

RAMIREZ: Right, right. Well, because, actually the climate has been pretty constant for the last 15 years. One thing I do like about that cartoon, you're going to have to buy the book to see it.

Is if you look very carefully in the very top it says E equals MC Hammer.

LAMB: Yes, I saw that. This is one from 2009, speaking of slavery, explain this one.

RAMIREZ: Oh yeah. This is on a government that's, that's taken on the role of being sort of the nanny state. you know, saying that, you know, stop, stop your wining. We'll, we'll provide for you, just do what we ask and if, and if you do exactly what we ask for, we might even provide you with some healthcare.

And so it's sort of the plantation mentality of a government that sort of oversees everything that we do. You know, I was up in New York and I was having breakfast.

And of course, that had a (city) person guiding me to make sure I didn't use too much salt on my eggs.

LAMB: 2011, this cartoon, is rather stark? What are you saying here?

RAMIREZ: Here you know I, I, I think -- when you think about Clarence Thomas, there's a lot of criticism with Clarence. And I mean -- I'm just going to use him as one example.

I love Clarence Thomas. Some of his writings are just amazingly depth -- in depth analysis of everything, and yet they criticize him, because he never asked questions during the Supreme Court hearings.

It seems to me that when you look at these conservative blacks, these conservative African-Americans, they ought to be models for the community. The mainstream media sort of negated who they are, or their -- their members within political organizations, they're negating who they are, because by virtue of what their skin color is.

You know, I'm half -- half Spanish, one quarter Spanish, one quarter Mexican, half Japanese, completely confused.

I think in the 21st century we've got to move beyond this kind of idiotic idea that race ought to be a determiner for anything.

You know, I've got -- we've discussed before, I've got two brothers and two sisters, and they're all extremely intelligent, kind people. The exact opposite of me, and we -- we come from the same genetic material. I think at some point, we're going have to discover that we need to move beyond these kind of issues.

LAMB: Let me go back to that cartoon just for a second, and tell you -- and some people listening to this program, I want you to explain what they're looking at.

RAMIREZ: What they're looking at is, back in the '50s, they discriminated against blacks by having refrigerated water for the whites, and then having these kind of very poor water delivery for the blacks.

I'm saying that there are certain political -- people within the political hemisphere that have done the same thing to conservative blacks, that kind of discrimination is going on today.

And the kind of things that they're allowed to say about people like Clarence Thomas, you know, like Ben Carson, I think is horrible.

LAMB: You might find this interesting -- this is, and I'm not sure I'm going to pronounce it right, his name is Borzou Daraghi, former L.A. Times Baghdad Bureau chief, back in 2007, talking about an Iraqi cartoonist.

Watch this.

(Begin Video Clip)

Borzou Daraghi: This is a very poignant one by (Houdar Hamajer), and it just shows a scene where a U.S. soldier is aiming a gun at an Iraqi guy, and then you have Uncle Sam drawing a portrait of this scene, but instead of a gun, he is handing the flower to the Iraqi guy.

You know, I asked (Houdar Hamajer) whether he thought that this sort of cartoon was inflammatory, whether it might cause too much trouble, and he sort of laughed at me, and he said, you know, "I go online and I check out the American cartoonists and the stuff they have about Bush and U.S. foreign policy and American domestic and international politics.

It's far more critical and far more nasty than anything I've ever drawn."

(End Video Clip)

LAMB: What do you think?

RAMIREZ: You know, it kind of reminds me of -- there are a bunch of us that got to visit with Ronald Reagan in the Rose Garden when he was president.

He had this wonderful joke where he said that -- he said, "You know, the difference we see in the United States and the Soviet Union is in the -- in the United States' political cartoonists can draw political cartoons on the president of the United States.

In the Soviet Union, the political cartoonists have to draw political cartoons on the president of the United States."

You know, that's the one thing that we have here that's -- that's so amazing about this country, is the freedom of speech and freedom of information that you can effectively criticize that run the government.

It really differentiates between who we are and what other countries are. We -- you know, a bunch of us went down to Cuba, Havana, Cuba.

And I had gotten the opportunity to talk to the information minister, and so, I asked him about questions about, you know, the brothers-in-arms flag that was shot in international air space, about the journalists that had been arrested, about the people that were handing out petitions simply to even talk about democracy that were arrested.

And he refused to answer any of those questions. And so, I said, well, let me ask you just one last question. You know, I talked to your reporters, and I talked to some of the cartoonists there in Cuba. And they're not allowed to draw images of Fidel Castro.

They cannot draw images of (inaudible). In America, we believe, you know, a country that cannot make fun of its leaders is usually a country that is imprisoned by its leaders.

So, I'm going to ask you this one question -- what's your favorite Fidel Castro joke?

And his face just went white, and little beads of sweat gathered on his forehead, and he finally said, I don't know one, but I will tell you one later.

That's the difference between the United States -- and this freedom that so many people have sacrificed for to ensure.

You know, we have boys -- men and women out there, that are fighting to guarantee our liberty and our freedom. This freedom that we take for guaranteed. I don't think any editorial cartoonist ought to -- I think it's a very cherished responsibility to use this freedom to educate the masses, to make sure that they understand that this government works for the people.

LAMB: He's a cartoon -- you've made some people who have an Iranian connection mad at you for this, and I don't know what you titled it, put it on the screen.

Call it The Cockroaches?

RAMIREZ: Right. Now, this cartoon received a lot of criticism. If you look at -- if you look very careful on the cartoon, on the bottom of the grill, it talks about terrorism, specifically about extremism within Iran, so.

LAMB: Let me just explain. It's the country of Iran.

RAMIREZ: Right.

LAMB: And it's got a sewer let over it, and cockroaches coming out of it.

RAMIREZ: Right, and on the sewer lid, I think it says, "extremism," although I can't read a bit.

It really is talking about a very specific segment of the population of Iran that is responsible for engendering these surrogates of evil, and spreading chaos within the region.

And you know, I did receive a lot of criticism, but what I said to that is, you know, Iran is responsible for a lot of the chaos that's going on. This kind of expansion of radical extremism, you know, it started in Iran first.

Hell, I mean, you could argue that the wahhabist in Saudi Arabia are also doing the same thing.

But these groups, when you look at the population, I think the average age is what, like 28, and they are very pro-Western. But the theological dictators of that regime and the Revolutionary Guard use these surrogates of evil to create chaos in the region.

LAMB: One of the things in this cartoon -- the cockroach cartoon -- is that it shows the cockroaches spreading to Afghanistan and Iraq and Syria, and even to Israel and the Gaza Strip.

RAMIREZ: Right.

LAMB: And Pakistan and all the countries around it. What made people the maddest about this?

RAMIREZ: Well, you know, I think the Iranians were mad, because I characterized the country as a whole as a refuge for cockroaches.

But I was very specific in the extremists, I think. You know, this is the one thing that people, I don't think realize, this expansion -- this Iranian expansion that is going on is very dangerous.

And when they become a nuclear power, you know, mutually, sure destruction only works when the other side doesn't want to die. And because of this -- this nuclear arms race that's going to be going on in the region. In a region that has lots of oil money, but very little reverence for human life, it's going to become a much more dangerous world.

One last one, this is the 2014 -- you see it on the screen, this is the World Trade Center, you have got people falling to their death, and the one fellow says, "How do you feel about enhanced interrogation?"

This will be our last one, so explain this one.

Right.

LAMB: This caused a lot of feedback, too, though.

RAMIREZ: It did, it did. And you know, I'm not afraid to -- of the feedback.

You know, there's a real question as to the responsibility of our intelligence services to figure out where are these dangers of terrorism are coming from.

And I think, because when you look at this war that we're embroiled in right now, this war on terror, it can only be effective if you know what's going on the ground. By taking away the devices that allow you to figure out what the machinery is that's generating this terrorism, you expose us to danger.

Now, we can debate about water boarding -- you know, our seals go through water board training, I don't think it's torture, frankly. But if you just blow up terrorists, and you don't find out who they are, how they're connected.

You know, the San Bernardino case, we've got their electronics, we can sort of put together a trail of who these people are, that's a much better way to secure our safety.

LAMB: I've only got 30 seconds, one last question. How did you get Dick Cheney and Rush Limbaugh to write the forward and the afterward?

RAMIREZ: Well, you know, I'm very honored to say that I've become friends with Dick and Lim -- Cheney. Some friends of mine had them over for dinner, and I got to meet them.

I've always been a fan of the vice president, and sort of his view on politics.

And of course, Rush, I've had a relationship with Rush for a long time, not only with Paul (inaudible), but prior to that, he used to run my cartoons in the Limbaugh letter.

LAMB: Besides buying this book for $28 dollars, where can people see you on a regular basis, besides Investors Business Daily?

MICHAEL RAMIREZ: Well, if you go to the website, www.investors.com/cartoons, you'll see my cartoons every single day.

You can get at Twitter, @ramireztoons. And on Facebook @michaelramirez-politicalcartoonist.

LAMB: The name of the book is "Give Me Liberty or Give Me Obamacare," Michael Ramirez, thank you very much for being with us.

RAMIREZ: It's a real pleasure to be here.

Latest Essays by Michael:

Sacrificing Kids …read more at michaelpramirez.com

Visit the T-Shirt Store, Prints @ Michael P. Ramirez Store (for special request art prints, please write to: ramireztoons@gmail.com) Original Website: michaelpramirez.com

Click on mylvrj.com/ramirez to enjoy two months of the Review-Journal for just 99 cents.